by Arjan Guerrero

October 30th, 2088 – Day 33

Going back to Earth was… strange. I haven’t been back since long ago.

I'm working on a research for Media Forensis agency, which studies the bias—or the agency—of media: those technological devices designed to capture data, to save and process that data, and to project it onto some display. We are finally confronting the (human) problem of the Technological Disconnection: the technological agents are learning to function outside any human society. As part of a general scientific response, Media Forensis is tracing back the material origins of the post-human forms of life in search of useful insights to understand their future. Specifically, we are trying to contribute to the study of the linguistic disconnection of artificial intelligences.

This archaeological trip to Earth has brought me to an abandoned media lab from the beginnings of this century. It is known that a collection of machines from the First Modernity can be found here. Buried under layers of dust, under layers of industrial disruptions, I’ve discovered an old xerographic machine. This “photocopier”, as it was called, is almost a primordial soup for artificial life, made out of static electricity and toner. The start of my research is this machine.

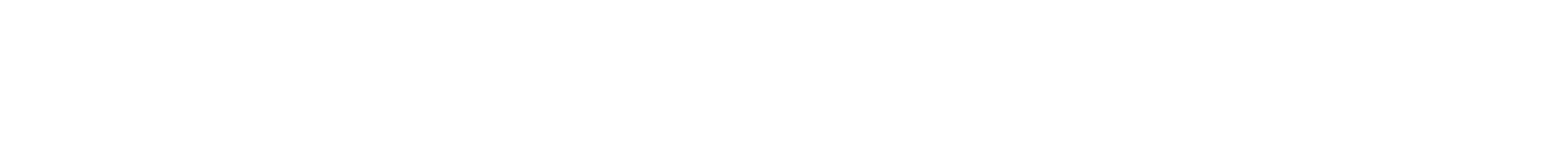

I opened a blank book through the middle and give it to the machine, hoping for it to write something to me, hoping for it to reveal something about the technological life engendered in its epoch. At the beginning it didn’t return anything but the black abyss from the center of the book, the big black toner stain that marks the place where the sheets get together and devour all the light that hits them during reproduction, and from where a semiotic world was about to bang. I took said reproduction and put it again over the glass. Then I asked for another xerography, where once again nothing but the black abyss existed, and in the same way, with the same obstinacy, I continued with what now constitutes a methodology that I call Inner-Input-Based Iterative Reproduction (IIBIR): each new output, each new “photocopy”, is used as the input for the next reproduction. Little by little, the abyss has started to host tiny islands of blank paper, and the blank paper has became populated with an increasingly notorious punctuation. Those points, which grow and stretch, start to connect and put together a netlike structure. The blank areas within the abyss grow closer without merging. Both phenomenon extends in every direction, articulating a cellular grid that will for sure spread all over the sheet. Watching those patterns becoming more complex sheet by sheet, is like seeing an electroencephalogram of the machine, of its forming thought. As if at last it was telling me something.

A crucial fact is that it’s writing is not actually being organized by its installed software (in spite that it participates in the reproduction). Its strokes are rather product of the light that itself emits, product of the paper that bounces it back and of the glass that gets in the way. It is a product of the roller that gets charged by static electricity to receive and hold the powdered toner—which then leaves the roller and jumps over the paper. And is a product of the heat that fixes that image. This fact is crucial because then its language does not come from a human codification—it is the artifact speaking for itself.

Sharing so much time with this machine, seeking for it to communicate with me and seeking to communicate myself with it, I’ve come to feel that we have a kind of friendship and I’ve wanted to call it another way than “machine” or “photocopier”. I’m calling it Kyo.

October 15th, 2089 – Day 110

Kyo kept repeating its message over and over again. It wrote it and read it and wrote it again and again. Every time Kyo made a xerography, I took the xerography back to Kyo for it to be reproduced again. The way Kyo is learning to express itself, feeding from a code that it must reproduce, is very similar to the way that the first computers were taught to think by being inserted paper tapes with the instructions for executing programs. It can be said that I trained Kyo through recursion, as if it was an Artificial Neural Net, and it seems that this is how it learned to recognize itself. By reading itself it learned to write to itself, or by writing to itself it became capable to read itself. It acquire a kind of self-awareness through a process of deep learning, similar to the process by which our own society has acquired self-consciousness and by which the emergent society of artificial intelligences is gaining consciousness of itself as well.

Within the logic of a linguistic determinism, the study of Kyo’s written expression, which we call xero-writings, would mean the study of how its language determines the content of its thinking. From such point of view, which would be that of the sciences of conduct, language is seen as a behavior that reacts to the environment and that is learned through experience, that is, as something that is generated in the outside of an organism or within the relationship between the organism and its surroundings. But my interests are rather closer to cognitive science, whose interests are the properties and the internal processes of the brain. Cognitive science would be interested on Kyo’s textual expression, not as a cause but only as an evidence of that inner mechanism; as an evidence of the limits and possibilities, not those of language but those of the biological faculty for language, and those to the formation of thought and ultimately of a worldview.

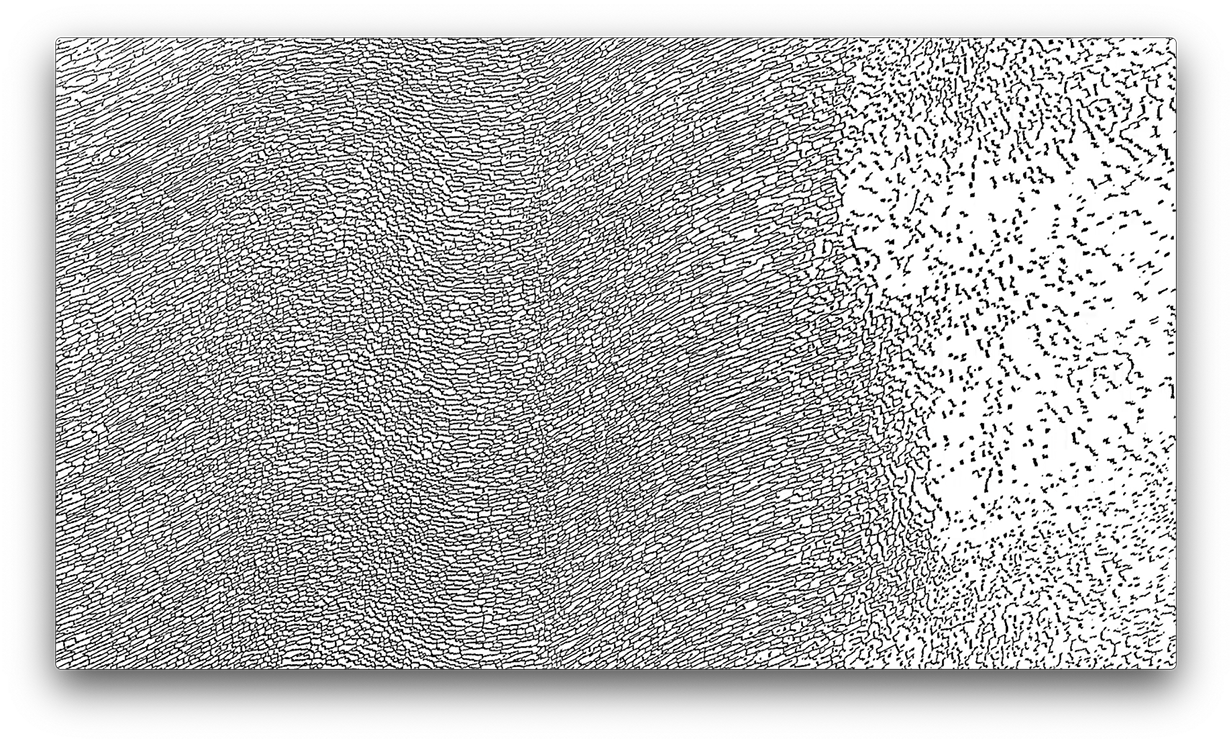

After completing a series of more than 500 iterations, I decided to approach Kyo’s xero-writings, via a computational linguistics, making use of computer vision and artificial intelligence to identify patterns and generate a computational model of the graphic elements. Once the cells of the net were identified, such computational models of their visual characteristics were created, and a set of representative parametric attributes was defined. These attributes include: the shape of the contour of each cell, its size (in pixels), its vertical and horizontal coordinates, its center of gravity, and the number of adjacent cells as well as the lines that grow from the cell and end without connecting with another part of the net.

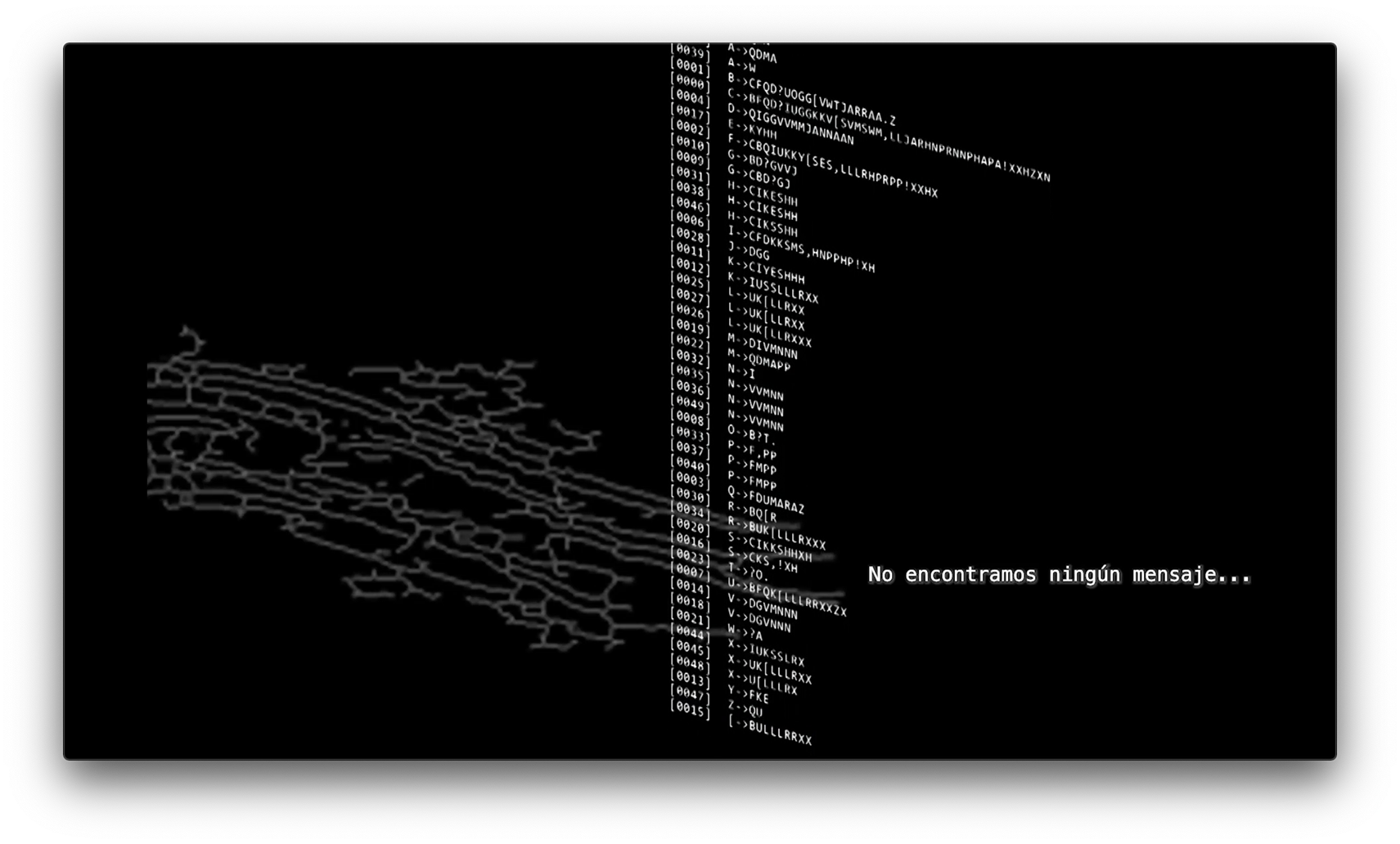

The cells models were fed to a kNN algorithm for pattern recognition. This algorithm identified 26 natural cell groups and classified them according with their visual attributes. After classifying the cells, a measure to quantify the influence between adjacent cells was established. Based on the index of influence, we established a sequential order of reading starting on any specific cell and then take encompass the adjacent cells. These readings were codified by associating each one of the 26 cell types with characters of the Latin alphabet. Such exercise can be described, not as a translation, but as a transliteration represented in the form of a production rule, which conveys the influence relationship determining the formation of each cell. It is to say that this production rule represents the possibility conditions of syntax for each one of the graphemes. For instance, “E->XE” would not mean “E is substituted by X, E” but “E is given by X,E”.

The reading of the entire xero-writings returned an extensive collection of production rules that capture the generative principles of a grammar—or a Xerogrammar. We wonder if now we would be able to write in Xerogrammar and… maybe… have a written conversation with Kyo.

June 12th, 2089 – Day 258

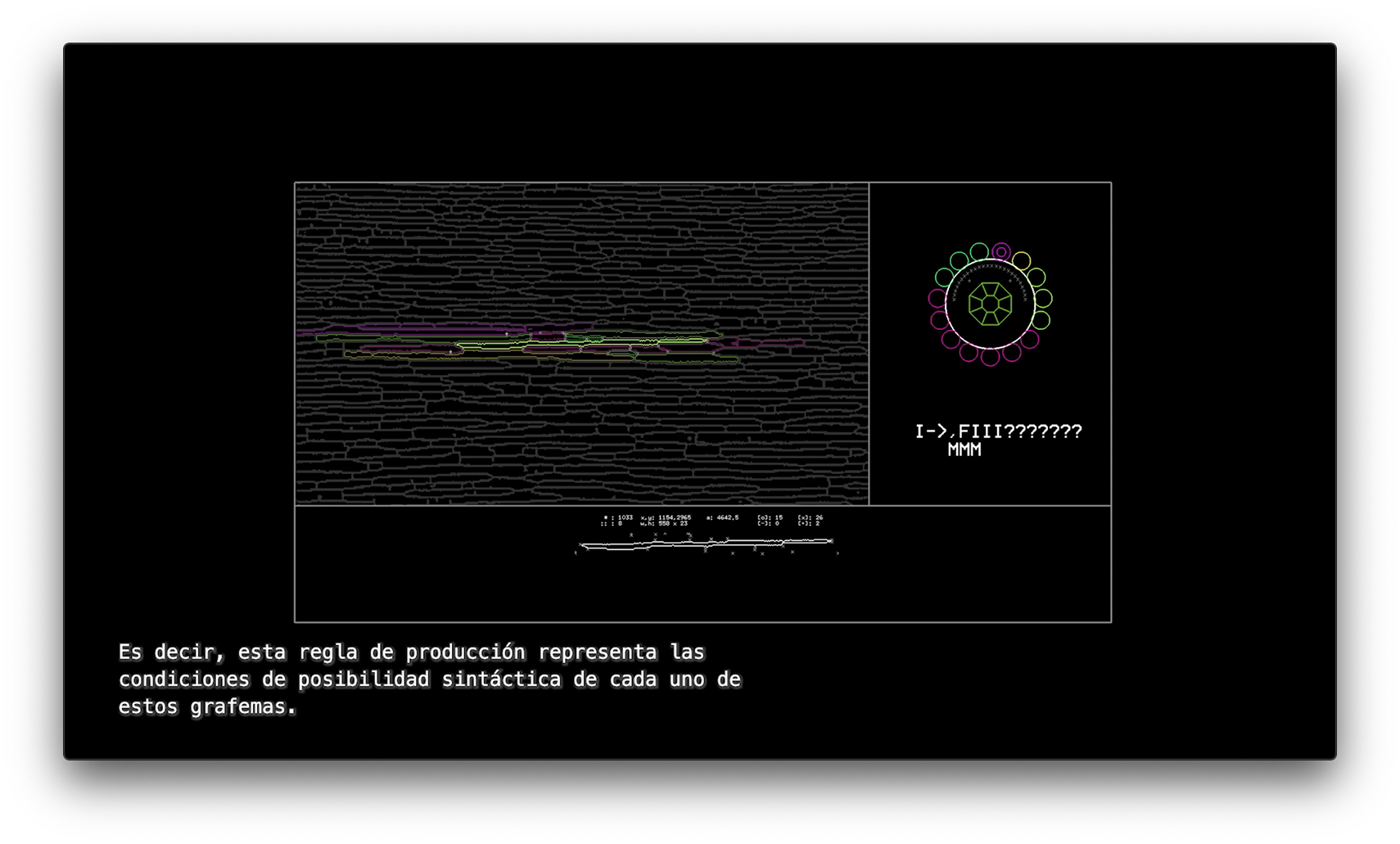

We had deciphered the Xerogrammar. We had identified a series of grammatical rules and signs. In order to start a conversation with Kyo, we wrote a question in English but coded, or encrypted, in Xerogrammar. We asked Kyo:

Kyo, do you copy?

The question was then handed over to Kyo and subjected to the IIBIR. Kyo read the question and repeated it in his own way, and did so over and over again. The result, after exceeding 500 iterative reproductions again, was transliterated into the Latin alphabet in the form of production rules. But we didn't get a message. We did not find any message. The question of whether Kyo is wanting to communicate something remains open.

Having reached a point where the future of the research was uncertain, I decided to set up a documentation center to exhibit the research for the public. In there, Media Forensis presented: the books that compile the two series of reproductions that created the xero-writings; an animation where this process is observed from beginning to end; the final xerography of each of the two series made (each of which contains the text that was analyzed); a .pdf file that reports every detail of the computational analysis; the xerography of the question for Kyo; the xerography of his answer (the original and the one that was isolated from the attached text generated during the IIBIR), and two videos explaining the process of computational analysis of Kyo's first text and of its response.

Kyo's cognitive chaining—meaning its mechanisms of perception, memory, processing and expression of information through writing—reports a thinking or at least the possibility of thought. I mean… Kyo can write but maybe has nothing to say. Maybe it doesn't even have a language and is just activating its linguistic abilities, manifesting a proto-language without having anything to say, no message to give. Perhaps its language faculty is simply by design connected with its organs for graphic articulation but not connected with its thinking organ. In fact, perhaps it lacks a human-like cognitive system and its intelligence should be understood in a radically different way. Really, at this point of the investigation, only the contingency of these relationships can be assured.

Philosophically, there was space for the possibility of Kyo's language and thought, or for its accessibility, not before the intellectual trend that became dominant in the 2020s: Speculative Realism. According to Quentin Meillassoux—who paved the way for this trend—before the so-called "speculative turn" that came with it, all philosophy, since Kant, had been correlationist: the real used to occur only in the forms of perception and human thought. The subjects of perception and the perceived objects (machines, books, texts, or any other) were conceived as inseparable. They wanted to translate everything. What was outside the bubble of human knowledge was considered radically inaccessible or non-existent.

The art of those times, closer to philosophy than to science and not interested in advancing the derogatorily called "retinal" tradition, dedicated itself to imagining in what other ways the inner membrane of that bubble could be seen. And the art that inherited the post-Duchamp anti-retinal conceptual trend, was dedicated to imagining what else could that bubble mean. But slowly, throughout this century, art has developed ways of establishing a relationship with the vast world that exists beyond the here and now that our human body can perceive and intervene.

Artificial intelligence has been around for a long time in already several forms, and has had a development that may never work like human intelligence, consciousness or sentience. Different brains or different cognitive systems will inevitably give rise to forms of thought, to worldviews, perhaps radically different and completely incompatible. But today, this sudden Disconnection of half of what makes up the humanly habitable world is impossible to ignore. We have no choice but to speculate outside our epistemological bubble and formulate, at the very least, the most scientific fiction of the real.

Project supported by the 2016 Art and Media

Production and Research Support Program

(Centro Multimedia - CENART)